Set in the sleepy coastal town of Bharathi Nagar, nestled somewhere between Akkarai and a forgotten beach, where time didn’t move fast—except, of course, when it came to gossip.

Raghu was not a man of noise. He didn’t speak much, nor did he mind when others did—though he wished the auto drivers wouldn’t honk quite so often when his coconut tree shed its bounty right onto their roofs.

He had once been an architect. A good one, by all accounts, though his designs were often called “eccentric.” There were murmurs at the Municipality Office that he designed a post office shaped like a seashell and insisted a marriage hall be aligned to Venus on Thursdays.

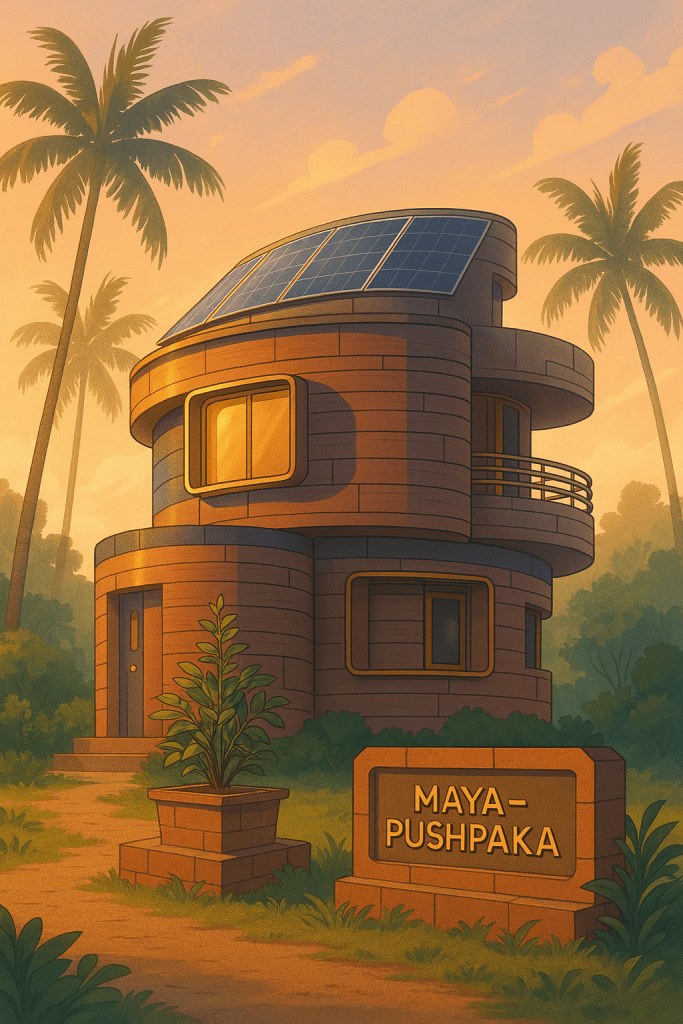

But now, in his retired life, Raghu lived quietly in a peculiar house that faced east on Mondays, slightly northeast on Wednesdays, and once, in a bold experiment, faced the beach sideways for an entire month.

“It rotates,” explained the milkman, more than once, to confused guests standing at the wrong gate.

The Talk of the Town

The house had many names. Some called it Mayakkam Veedu—the dizzy house. Children referred to it as Raghu Sir’s Merry-Go-Home. But the name carved onto the wooden plaque at the entrance read simply: Maya-Pushpaka.

“Like Ravanan’s aircraft?” asked the postman one evening.

“No, no,” said Raghu, stirring his filter coffee. “This one doesn’t fly. It listens.”

“Listens?”

“Yes. To the wind, to the stars, to the soul.”

The postmaster decided to avoid further questions.

A House With a Mind

The house could shift its mood. On rainy days, the balconies pulled themselves in, like a lady adjusting her saree pleats. When summer came, the walls breathed out cool air through woven coconut-coir vents. And at precisely 5:40 a.m., the prayer chime would ring—not by clockwork, but by the alignment of the sun and Saturn.

Neighbors thought he was mad.

But Raghu had never been more sane. After his wife Meenakshi passed, he found himself alone—but not lonely. She had left behind something remarkable.

Inside the prayer room, hidden behind the Ganesha idol, was a small touch panel. When he activated it, the house played Meenakshi’s voice:

“Don’t forget to rotate the bedroom toward Jupiter on Thursdays, Raghu. You sleep better when your dreams are aligned.”

Visitors and Doubts

When his niece, Priya, a software designer from Bengaluru, came to visit, she looked around suspiciously.

“Maama, why can’t you just live in a normal apartment like others?”

He smiled.

“If I wanted to live like others, I would have built walls. But I built windows.”

She rolled her eyes. “One day this whole thing will fly away with you, I swear.”

“I hope it does,” he replied.

The Cosmic Twist

On the 11th night of the Panguni month, the house rotated precisely 78 degrees to align with Mars. The coconut tree in the backyard cast a different shadow. The sea breeze changed direction. And for the first time in weeks, Raghu dreamt of Meenakshi—not in memory, but in motion.

In the dream, she stood on the balcony, hair swaying, smiling.

“This house was never just shelter, Raghu. It’s the body of your rhythm. Let it dance.”

The Ending? Or the Beginning?

The thief’s encounter

The Maya-Pushpaka doesn’t just hide the entrance—it actively messes with Kannan, using its rotations, shifting walls, and cosmic quirks to confuse him..

Every time Kannan approaches the gate, the house rotates slightly, so he’s facing a blank wall or a coconut tree instead.

By dawn, Kannan was halfway to the next town, swearing never to rob a house that “doesn’t even respect gravity.” The milkman, spotting a lone screwdriver by the gate, shook his head. “Maya-Pushpaka’s at it again. Poor guy probably thought he could outspin Saturn.

The next morning, the milkman saw something strange. The house had turned again, now perfectly aligned with the sunrise, and a soft hum was coming from the walls. He claimed the very air around it had a scent of vetiver and jasmine.

The milkman took a deep breath, nodded, and walked on.

For Bharathi Nagar, it was just another Tuesday.

But for Raghu and his Maya-Pushpaka, it was a perfect alignment—not of structure and soil, but of memory and meaning.

Leave a reply to Bhaskar Natarajan Cancel reply